Could a chemical found in many household products help alleviate fashion’s microplastics problem?

Synthetic textiles shed countless plastic particles that ultimately end up in the ocean, but a research lab at Canada’s top university may have found a solution

This article was originally published on theguardian.com as part of the University of Toronto and Guardian Labs What’s Possible? Ask Toronto campaign.

Fashion is one of the highest polluting industries in the world, and one of its biggest problems is microplastics. These tiny particles are shed from synthetic clothing during washing, and it is estimated there are now trillions of microplastics in our oceans.

The DREAM Laboratory at the University of Toronto’s Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering is working to tackle this. Its team of engineers uses chemical coatings or additives to change how surfaces behave, often with dramatic results, and one of its latest discoveries is a chemical that can make the surface of textiles more slippery, making the microplastics less likely to break off.

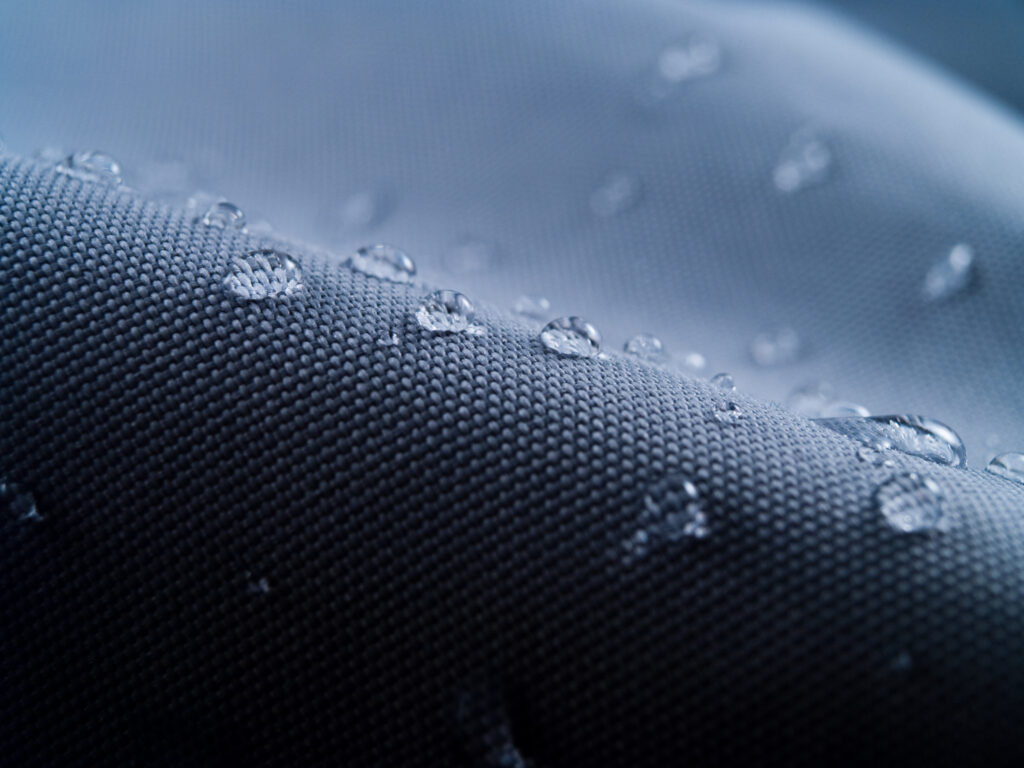

Microplastics are a particularly big problem for fast fashion companies, which produce a high number of items made of synthetic nylon, polyester, acrylic or rayon. These materials constitute about 60% of all new garments made today, according to the UN, and every time they are washed, the friction caused by washing machines causes tiny tears in the fabric and small fibres to break away. These fibres, measuring less than 500 micrometres, are washed down the drain to enter waterways. As they accumulate, they threaten marine life, and have made their way into the human food supply and tap water. They tend to facilitate the transfer of contaminants along the food chain, with potentially grave consequences for human health.

Attempts to stop microplastics have so far centred around filtering them out, using either filters placed into washing machines or clothes-washing bags that collect the tiny fibres. But Dr Sudip Lahiri, a postdoctoral researcher at the DREAM Laboratory, has discovered a new way to tackle them.

“As a textile engineer by trade, I developed a molecular primer based on my understanding of fabric dyes,” says Lahiri. “I thought that a low friction fabric could reduce how many microfibres come off. It turned out to be correct.”

“One of the areas we’re working on is replacing forever chemicals in textiles – the hazardous fluorinated stuff that is on waterproof apparel,” says DREAM Laboratory head Prof Kevin Golovin.

The coating in question is made from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) brushes, a silicon-based inorganic polymer that is found in many household products. The substance is quite slippery, and the team found that coating textiles with it led to significantly reduced microfibre shedding after repeated washes.

Originally, the goal was to explore the use of PDMS as an alternative to waterproof coatings that contain toxic “forever chemicals” – so called because they do not break down in the environment – which were found in 2022 to be in 75% of stain or water-resistant clothing. That work is still ongoing, says Golovin. “We haven’t quite yet achieved the oil repellency requirements that the forever chemicals have right now, but if we are successful that’s a huge avenue for the coating.”

He adds that the current replacement non-fluorinated alternatives that some brands already use for waterproofs are not great for the environment either, because they are based on palm oil, which is linked to deforestation. “So this could be an alternative for those as well,” he says.

The next step for the team’s microplastics work is creating a process suitable for industry use. “The way in which we apply it to textiles is probably not the way that a large textile mill would apply it at scale,” says Golovin. “At the moment, we’re trying to transition into something that industry could easily adopt, so they don’t have to invest in millions of dollars of equipment just to apply the coating. We’re hoping to finish that work by the end of this year.” After this, the plan is to find a sustainability-minded textile brand to work with and champion the technology.

Golovin says brands have a range of reactions to the idea. “I’ve talked to quite a few brands and some are very interested. Others recognise it’s a problem, but don’t care. Without some sort of legislative ruling, I don’t know that they would be motivated to change.”

Golovin’s new coating offers brands and manufacturers a straightforward way to dramatically reduce their environmental impact. With an industrial process on the way, it offers hope that one of the clothing sector’s major sources of pollution could be tackled.

Find out how U of T Engineering has driven change and innovation for more than 150 years at 150.engineering.utoronto.ca

By Rebecca Thomson